Management Strategies

Before addressing the suggested management strategies, we will make a few brief comments about public participation and involvement in decision making. Public participation in decision making may take multiple forms, including participatory democracy, in which citizens play an active and direct role in decisions, and representative democracy, in which citizens express their will through representative interest groups (Overdevest, 2000). There are at least three rationales for public participation in management (Appelstrand, 2002). First, it may provide more information for government stakeholders. With greater participation, more interests have the chance of being represented and therefore decisions will tend to be more inclusive. By making the process more inclusive, fear and accusations of the process getting captured by special interests are less likely. Second, public participation conforms to the ideal of a basic human right to be involved in decisions concerning public goods like the environment. And third, public participation can bolster the legitimacy of decisions and of agency actions. Decisions that are regarded as legitimate are more likely to be supported, by both the public and by the courts. Legitimacy conferred by public participation also indicates transparency, fairness, and the opportunity for every citizen to be involved in decisions and planning (Appelstrand, 2002).

A natural resource manager or agency needs to decide what level of public involvement to encourage. At the least integrated level, there are diagnostic and informing approaches, designed to elicit information from public stakeholders in order to better understand their desires and attitudes. This information is then used to help decision makers understand issues more fully and include local attitudes in policy deliberations. A second level of participation involves co-learning, in which stakeholders have the opportunity to acquire new information that may lead to changes in their perspectives and ideas. These new or modified public perspectives and ideas will subsequently be included in agency deliberations about planning and policies. And the most integrated level of public participation involves all parties co-learning and co-managing, with direct involvement of public stakeholders in the decisions being made (Lynam, de Jong, Sheil, Kusumanto, & Evans, 2007). The first level of public involvement, where information is elicited from public stakeholders, is primarily a means to improving the efficiency of management decisions, while the last and most integrated level suggests a process more inclined toward the ends of political involvement, empowerment, and equity (Mannigel, 2008).

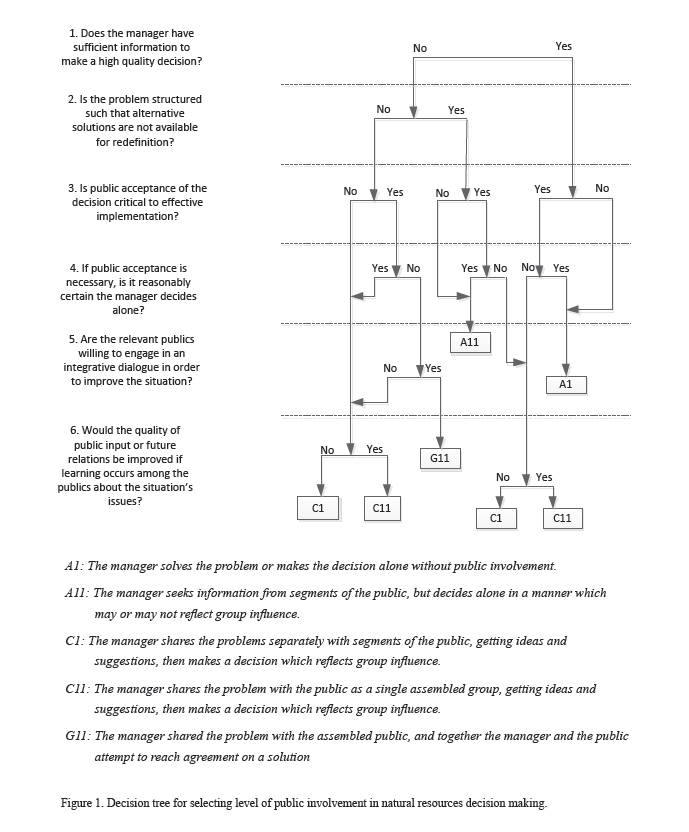

The suggested strategies that we have proposed primarily constitute the first level of public involvement described above - information was obtained through a public opinion survey that can help managers better understand public attitudes and perceptions of urban forest ecosystem services in order to support efficient management. The management strategies discussed in the following sections may not be suitable for all situations. Different levels and types of public involvement may be better suited to your particular needs. In an effort to assist urban natural resource managers in deciding what level of public involvement might best be suited to their situation, we have provided the following decision tree proposed by Lawrence and Deagen (2001).

Figure 1: Decision tree for selecting level of public involvement in natural resources decision making

The original version of the model in Figure 1 was developed for private sector managers to determine at what level subordinates in the organization would be involved in decision making. Lawrence and Deagan (2001) refined the model for application in natural resource decisions to help managers find a suitable level of public involvement in decision making. The model is a series of yes or no questions the manager will ask her/himself to help gauge the level of public participation desired or required.

The first two levels of questions require a bit of clarification. At level 1, the manager must ask her/ himself whether s/he has enough information to make a high quality decision - defined as "a well- reasoned decision, consistent with available information and with organizational objectives and goals" (Lawrence & Deagan, 2001, p. 861). The second level question relates to the goal of making objectively better decisions through exchanged knowledge and improved definition of the issues involved. Questions one and two were developed in recognition of the fact that someone other than the manager directly responsible for the resource may be the final decision maker. The remaining questions are self-explanatory.

The management strategies we present next were developed through consultation with natural resource managers and can roughly be thought of as falling under the levels A11 or C11 in the decision making model (Figure 1) constituting the least integrated level of public involvement. Though the strategies suggested do not constitute direct public involvement in urban forest resources decision making, we expect that under the appropriate conditions they will be helpful for managers. The strategies suggested herein may also function as initial steps to creating more inclusive and participatory management and decision making in the future.