Literature Review/Background

In the early decades of the 20th century, biological scientists began to recognize the relationships that exist in nature as a network of ecological systems (Lindeman, 1942). Patterson and Coelho (2009), in a succinct synopsis of the history of the ecosystem services concept, suggest that it began to be formalized among scientists in the 1970s, and that by the early 2000s, the notion of ecosystem services was fairly well developed. Between 1991 and 2012, 3770 research papers focusing on ecosystem services were published throughout the world (Molnar & Kubiszewski, 2012) reflecting the considerable importance ecosystem services have for researchers and the public. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005, which describes ecosystem services as the benefits people obtain from ecosystems, signaled that the concept had become well established among scientists. Ecosystem science and research has continued to expand and evolve, more recently looking particularly at human dimensions of ecosystems and natural processes.

Defining Ecosystem Services

One of the hurdles complicating the ecosystem services concept's successful integration into natural resource management is the numerous definitions of the term (de Groot, Wilson, & Boumans, 2002; Fisher, Turner, & Morling, 2009). For example, Daily's definition (1997) refers to natural conditions and processes that benefit humans. Costanza et al.'s (1997) definition differs somewhat, referring to the functions ecosystems provide that humans enjoy. Fisher, Turner, and Morling (2009) provide an excellent discussion of the varying ways in which ecosystem services have been described. They discuss the various terms and language that have been applied to ecosystems and the services they provide, identifying how terms have generally fallen into categories referring to the organization of ecosystems, their operation, and the outcomes of ecosystem functions, and how these all relate to benefits available to humans.

Despite differences, a common theme that permeates the various definitions of ecosystem services is that people derive benefits (i.e., goods and services) from the structures and processes found in the natural world. Acknowledging that there is some disagreement on precisely how to define ecosystem services, this study adopts the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005 definition of ecosystem services as the benefits people obtain from ecosystems. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005 places the services into four categories: provisioning, regulating, cultural, and supporting services.

Provisioning services generate goods or serviced directly consumed by people. These include food, fresh water, fuelwood, fiber, biochemical and genetic resources.

Regulating services are benefits obtained from the regulation of ecosystem processes. These include climate regulation, disease regulation, water regulation, water purification, and pollination.

Cultural services are non-material benefits including spiritual and religious, recreation and ecotourism, aesthetic, inspirational, educational, sense of place, and cultural heritage.

Supporting services are those that indirectly benefit people because they are necessary for the production of all other ecosystem services. They include soil formation, nutrient cycling and primary production (MEA, 2005).

The effort researchers have expended at investigating ecosystems and the services they provide has contributed to a growing awareness among natural resource professionals and decision- makers of the vital importance of healthy ecosystems to environmental and human well-being. Researchers looking at ecosystems have historically come principally from the natural sciences and economics (Chan, Satterfield, & Goldstein, 2012). The work by natural scientists and economists has undeniably contributed powerful tools to help us understand and better manage Earth's remaining natural resources. Though the research to date has contributed greatly to sustainable natural resources management, it presents an incomplete picture of the relationship between humans and ecosystems. For instance, we currently know relatively little about public attitudes and perceptions of ecosystem services, especially in urban and urban proximate areas (Chan et al., 2012; Chan, Satterfield & Goldstein, 2012; Gobster & Westphal, 2004; Jim, 2011).

Natural resource managers need to incorporate a comprehensive understanding of the public's attitudes and perceptions about ecosystem services into management. According to Bright, Cordell, Hoover, and Tarrant (2003), "integrating social science information into the decision- making process and weighing it equally with information from the biological and physical sciences produce [sic] balanced solutions" (p. 12). This may be especially true in urban settings where humans and natural elements are in close and persistent contact. Currently, however, there remains a relative lack of research and information on public attitudes and understanding about ecosystem services (Smith et al., 2011).

With an understanding of variations in urban residents' attitudes and behaviors, managers may be better able to communicate with members of the public and integrate them more fully in decision making. Incorporating an enhanced understanding of public attitudes and perceptions about urban natural areas and the ecosystem services into management decisions can lead to objectively better decisions (Lawrence & Deagen, 2001), increased trust in agency activities (Parkins & Mitchell, 2005) and lessen the likelihood of legal challenges (Irvin & Stansbury, 2004), all of which benefit resource managers and the public. Technical information is an important contributor, but should not be relied upon exclusively and to the exclusion of information concerning public values and perceptions (Barro & Dwyer, 2000; Ryan, 2011).

Human/Social Component of Ecosystems

Though people in modern industrialized countries sometimes overlook their connection with the natural environment, we are inextricably linked to our natural surroundings (Wilson, 2006). How we individually and collectively behave in relation to the other components of ecosystems has a direct bearing on ecosystem function and our own health and well-being (Alberti, Marzluff, Shulenberger, Bradley, Ryan, & Zumbrunnen, 2008; Gill, Handley, Ennos, & Pauliet, 2007; Harrison & Burgess, 2008; Michalos, 1997). Research has revealed for example, that presence of natural spaces is associated with improved human health and longevity (Maas, Verheij, de Vries, Spreeuwenberg, Schellevis, & Groenewegen, 2009; Poudyal, Hodges, Bowker, & Cordell, 2009; Takano, Nakamura, & Watanbe, 2002), better psychological well-being and mental function (Hartig, Mang, & Evans, 1991; Korpela, Ylén, Tyrväinen, & Silvennoinen, 2010; Ryan, Weinstein, Bernstein, Warren Brown, Mistretta, & Gagné, 2010), and socially healthy neighborhoods (Baur, Gómez, & Tynon, 2013; DeGraaf & Jordan, 2003; Francis, Giles-Corti, Wood, & Knuiman, 2012; Peters, Elands, & Buijs, 2010). Absence of green spaces and landscape fragmentation in cities has been linked to less individual and community well-being (Byrne, Wolch, & Zhang, 2009; Di Giulio, M., Holderegger, R., & Tobias, S., 2009). There does appear to be a connection between human well-being and ecosystem health (Forget & Lebel, 2001; Horwitz & Finlayson, 2011; MEA, 2005), a relationship that strongly suggests researchers and natural resource professionals should explicitly incorporate human beings into ecosystem management.

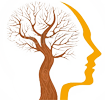

The human/social component of ecosystems has been integrated into a model of ecosystems in different ways. For example, van Oudenhoven, Petz, Alkemade, Hein, and de Groot (2012) discuss the challenges of integrating ecosystem services and land management decisions that link human needs and actions with the biophysical world. They propose a model that identifies the interactions between land management, ecological processes, and ecosystem services. The authors suggest a framework for selecting indicators of the link between ecosystems and land management actions that explicitly includes human components (Figure 2).

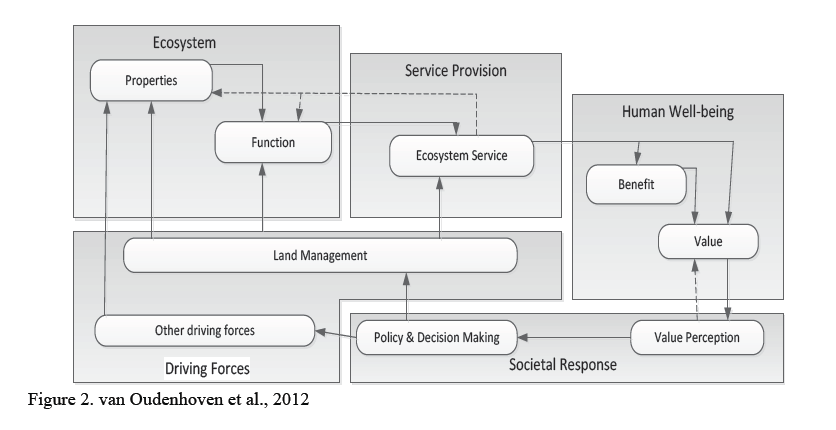

In van Oudenhoven and colleagues' model (2012), human actions and perceptions are clearly and explicitly included within a larger system of relationships between human and biophysical actors. In a similar fashion, de Jonge, Pinto, and Turner (2012) propose a model that seeks to integrate both human and biological systems to better understand their relationship. The authors suggest that this should be carried out at the habitat level, where the biophysical, social, and ecosystem service aspects can be more easily identified and measured (Figure 3).

de Jonge, Pinto, and Turner suggest that using this model will provide a holistic and integrated understanding of the relationships among human economic activities and social factors, biodiversity, and ecosystem functioning. The model would permit decision-makers to act with full knowledge of all the social, economic, and biological values at stake.

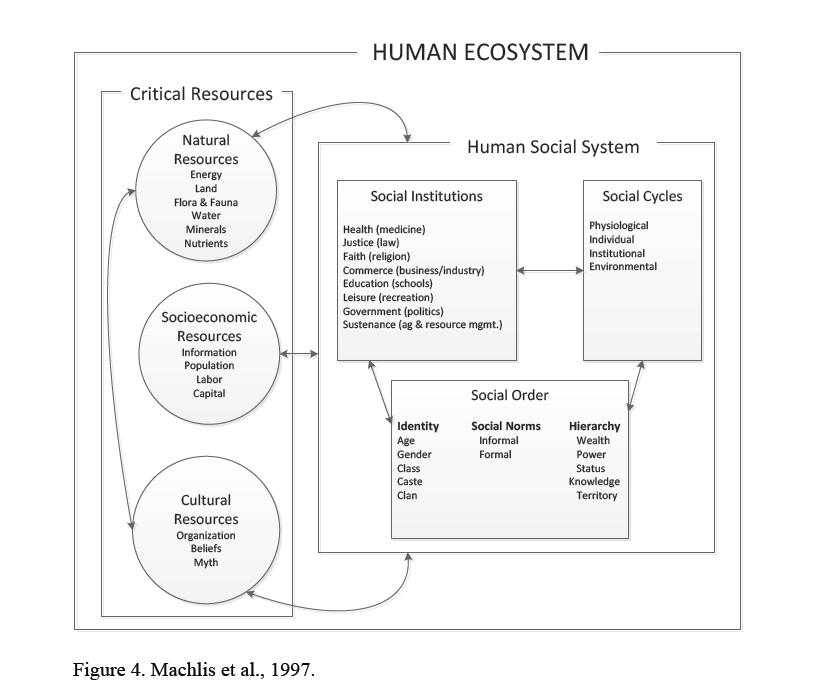

Machlis, Force, and Burch, Jr. (1997) similarly proposed a model in which human agency and influence were deliberately and explicitly included in the conception of natural systems. Machlis and his colleagues argue that natural resource professionals need to take greater stock of human behaviors and demands given that natural resource management is entirely a consequence of human creativity. They argue that traditionally, the biophysical and social sciences treated human beings as outside the natural system, as external forces that were somehow at best weakly tied to biophysical realities. Machlis et al. argue that responsible management of natural resources for sustainability is only possible when both the social and biophysical sciences receive equal weight in any consideration of ecosystem management. Machlis et al. proposed a model that, like the two previous, explicitly links human agency, institutions, and systems to biological systems, in a holistic model they call the Human Ecosystem (Figure 4.)

Machlis, Force, and Burch, Jr. (1997) suggest that their proposed model could be used to develop social impact assessments to be included in ecosystem management plans. Such assessments would define the full range of possible management impacts, on both the ecological and human components. The model could be used as a guide for developing social impacts indicators as part of ecosystem management plans and would facilitate adaptive management. Machlis et al., suggest their model could be used to help monitor other types of government programs or activities that affect not only natural resources but also human components. The model could be included in teaching and training of natural resource managers, and could help with a general practical and theoretical integration of social and biophysical sciences in an effort to more efficiently manage resources and provide for human needs.

As the three models we briefly describe highlight, humans should be considered an integral part of "natural" ecosystems, just as the other animals, plants, the air, soil, and water are considered part of the ecosystem (Force & Machlis, 1997). Acknowledging the place of humans in the ecosystem concept, natural resource agencies will be ignoring a substantial component of the ecosystem by omitting human beings from their planning and management of natural resources. To omit the human element from natural resource planning is perhaps particularly ill-advised in urban and urban proximate settings, where human beings are found in dense concentrations and have an immediate impact on the natural world around them. Urban areas may not at first glance appear to be ecosystems to many people, but they are clearly systems in which natural processes are at work and in constant negotiation with human systems (Pickett, Buckley, Kaushal, & Williams, 2011; Young, 2010). Human behaviors and actions can have a substantial impact on urban nature (Escobedo, Kroeger, & Wagner, 2011; York, et al. 2011) but urban natural features also impact humans. In some cases, the nature component of urban ecosystems imparts a positive benefit for people (Donovan & Butry, 2010). But natural features in cities can also produce negatives and costs including allergens, damage to personal and public property, places for "nuisance" species to live, create irritating sounds or smells, and create personal safety concerns from heavily overgrown and poorly maintained areas (Lyytimäki & Sipilä, 2009). Considering how heavily integrated natural resources and human systems are in urban areas, managers and researchers must improve their understanding of city residents' attitudes, understanding, and reactions to urban ecosystems and to natural resource management.

Attitude and Environment

Attitudes are a key influence on behavior (Ajzen, 2001; Ajzen & Fishbein, 2000) and are important to understand and account for in natural resource management (Hansla, Gamble, Juliusson, & Gärling, 2008; Larson, 2009; Schultz, Gouveia, Cameron, Tankha, Schmuck, & Franěk, 2005; Vaske & Donnelly, 1999) because natural resource management decisions often involve issues of individuals' freedom, property rights, and governmental regulation (Bright, Barrow, & Burtz, 2002; Bright & Manfredo, 1996; Larson & Santelmann, 2007,/a>). Despite the relationship between peoples' attitudes about natural resources and their responses to management actions, people's attitudes about natural resources management have been largely overlooked (Gobster & Westphal, 2004; Young, 2010). Public attitudes can help guide management strategies (Hansla et al., 2008), help craft tools for public awareness and outreach (Owens & Driffill, 2008), and be used to encourage sustainable use of our remaining natural resources (Leiserowitz, Kates, & Parris, 2006).

Since the early 1900s, attitude has been suggested as a key contributor to understanding behavior and, indeed, is considered by some to be among the most important concepts in social psychology (Crano & Prislin, 2008; Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). In their comprehensive text on attitudes, Eagly and Chaiken (1993) defined attitudes as "a psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor" (p. 1). The attitude concept has been helpful in explaining responses to natural resources management and conservation behavior. Oh & Ditton (2009), for example, looked at how recreationists' attitudes about conservation might differ based on their level of specialization (defined by behavior, skill level and knowledge, and level of commitment to an activity) and by ethnicity. The authors found that recreation specialization and ethnicity were both significantly related to conservation attitudes. Oh and Ditton suggest that one of the major benefits of their study is to help managers understand how anglers will respond to more or less controversial management actions, based upon certain characteristics. That is, based on specific levels of recreation specialization and ethnicity, managers may be able to better predict how people will respond to their management actions.

Bright, Barro, and Burtz (2001, 2002) examined the relationship between attitudes and ecological restoration in cities in the U.S. and abroad. The authors used a model of attitude formation that proposes attitudes are the outcome of three components - a cognitive, an affective, and a behavioral. The authors added a fourth component, issue importance, to the model. Bright and colleagues found that positive and negative attitudes were associated with the idea of ecological restoration, and that attitudes were differently influenced by the components. Other studies have also found a link between environmental attitudes and natural resources management and conservation (Barr, 2007; Bright & Manfredo, 1996; Fujii, 2006; Heath & Gifford, 2006; Larson, Green, & Castleberry, 2011; Vermeir & Verbake, 2006). Incorporation of public attitudes into natural resources decision making may be especially important when the management actions involve resources issues that are controversial or arouse strong feelings (Davenport, Nielsen, Mangun, 2010; McFarlane, Stumpf-Allen, & Watson, 2007; Vaske, Needham, Newman, Manfredo, & Petchenik, 2006).

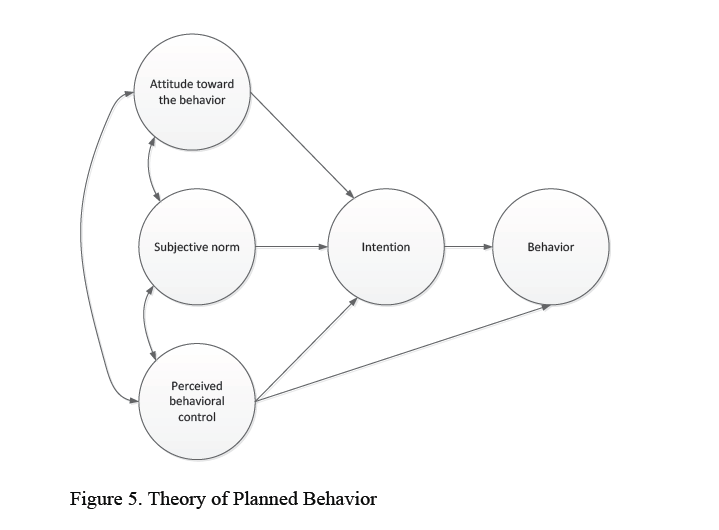

Research on the human dimension of natural resource management strongly suggests a connection between attitude and behavior, but the structure of the relationship is also important to identify. Various conceptions of how attitudes and behavior are related have been proposed, but have often failed to adequately account for the behaviors of interest to researchers (Crano & Prislin, 2008). A direct link between attitudes and behaviors has not been supported by empirical research, so researchers have proposed layered or hierarchical models in which attitude is an essential component (Johnson & Boynton, 2010). One such model, Ajzen's Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991) based on Fishbein and Ajzen's Theory of Reasoned Action (1975), has been used extensively to explain behavior. The TPB identifies factors that are linked to a specific behavior which act as intermediaries between a specific behavior and more general underlying traits.

The TPB argues that human behavior is principally governed by three antecedent beliefs. First, there are beliefs about consequences of the behavior. The combined beliefs about consequences form a favorable or unfavorable attitude about the behavior. Second, a person holds normative beliefs about what others expect. These normative beliefs, or subjective norms, result in social pressure concerning a behavior. Finally, there are beliefs about conditions that may hinder or support successful engagement in the behavior. These are control beliefs, related to an individual's perception of how easy or difficult it will be to engage in the behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 2000). The combination of attitude about the behavior, subjective norms, and control beliefs results in an intention to engage in the behavior (Figure 5). Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) argue that intention to engage in the behavior acts as an intermediate factor between antecedent beliefs and final behavior. That is, a combination of favorable attitude with positive social norms, and a strong sense of being able to engage in the behavior leads to a strong intention to engage in the behavior.

Fishbein and Ajzen's theory of planned behavior has been influential because of their more nuanced explanation of the relationship between attitude and behavior (Schwarz, 2007). Instead of drawing a direct connection between behavior and attitude, which research has not always supported (Fazio, 2007), Fishbein and Ajzen's research indicated that attitude is a key contributor, but multiple factors influence one's intention to engage in a behavior, and finally engagement in the behavior itself. Because of its success at accounting for variations in behavior, their theory has been employed in a variety of studies from those looking at physical behavior (Armitage, 2005), to levels of volunteerism (Greenslade & White, 2005), to the likelihood of getting a mammogram (Tolma, Reinenger, Evans, & Ureda, 2006).

Social psychology researchers argue that the nature and operation of attitudes, and the effect they have on behavior, are important if we are to understand how humans interact with each other and with their surroundings (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993; Olson & Kendrick, 2008). Researchers in various fields have successfully employed the concept of attitudes to help explain social phenomena, from consumer behavior and economic beliefs (Arvanitidis, Lalenis, Petrakos, & Psycharis, 2009; Kim & Choi, 2005), to children's environmental orientation (Larson, Green, & Castleberry, 2011). For urban natural resource managers who face a highly complex working environment in which people and natural features are in constant contact (Barro & Dwyer, 2000; Di Giulio, Holderegger, & Tobias, 2009; Dobbs, Escobedo, & Zipperer, 2011), acquiring a better understanding of the public's attitudes about resource management actions and incorporating that knowledge into planning and decision making will become ever more important as more and more Americans move to the country's expanding urban centers.